Every morning in Normandy we woke to the clear bells of the Bayeux Cathedral, consecrated in 1077 and one of the finest cathedrals in the world. I would retrieve our clothing, hand washed in the sink the night before and then placed on the metal bars of the electric towel warmer overnight to dry, which worked gratifyingly well.

Then we would walk past the beautiful cathedral and up the slant of a street to a little open air café, Le Maupassant. This was our breakfast spot. There we would be served by a white-haired, bright eyed gentleman of quick, small movements, his reading glasses always perched atop his head.

He would bring us deux cappuccinos with a thick dusting of chocolate atop the crown of foam and then croissants, buttery golden, which he brought to us from the pattiserie next door, and des œufs (eggs) au bacon. He was always cheerful, constantly in motion, and we cherished his sing-song 'Bonjour!' and 'OK, OK,' and 'merci!'

Who wouldn't love the pastry grenouilles (froggies)?

Never underestimate the power of carbohydrates with a good smattering of fat (the French don't make their carbs any other way) to give you the fortitude to face just about anything. These breakfasts, along with the idyllic surroundings and incredible evening meals, gave us the balance we needed for the emotional and sometimes exhausting stories we heard from 1944.

A slightly older tale of war and triumph, nearly a thousand years old, comes from the Bayeux Tapestry, a must-see in Bayeux. So famous it is parodied on The Simpsons in one of their "opening couch" scenes showing the battle between the Simpsons and (ha ha) Flanders who ends up chopped to pieces, the couch restored to the rightful owners. Nearly 225 feet of linen, not actually a tapestry at all, it is embroidered with the story of the Norman conquest of England, of Harold and William the Conqueror,

(look! Camels! Up at the top there!)

one rip-roaring tale of battles, betrayal, kings and successions. Yes, soldiers chopped into pieces, arrows and swords and some fellows no one mentions who seem to have forgotten their clothing. Hailey's Comet makes an appearance, foretelling doom, in this case for Harold in the Battle of Hastings, 1066. Some call it the earliest comic strip, and it's thought that the Bayeux Tapestry was brought out on special occasions and displayed within the cathedral or in Notre Dame in Paris for the education and enjoyment of the people.

During the French Revolution, when cloth was scarce, The Bayeux Tapestry narrowly escaped being used as an ox-cart cover, at which point the French decided it was a national treasure. Napoleon cited it as his inspiration not to invade England, and during the World Wars it was hidden from the invading armies in the Louvre.

We were fortunate that it now resides back in Bayeux, so we paid the thousand year old tale a visit. When you go into the museum they give you earphones and a guide recording -in the language of your choice- and you walk and walk along the Tapestry, as prompted to the different scenes by the narrator, and then go around the corner and keep going, the Tapestry beneath glass and illuminated by special lights to help preserve the colors and fabric.

Back in the day it must have been the highlight of the year to go see the Tapestry, better even than waiting for a Charlie Brown special at the holidays.

Personally, I love the trees (there on the right), and the way the armor of the soldiers is depicted as little groupings of circles. Those curly crowned trees have been adopted as the symbol of Bayeux; you see them reproduced everywhere.

There is a very special tree in Bayeux, one that we hadn't grasped the significance of until later. In Place de la Liberte, arching next to the cathedral is this wonderful old tree with gnarled roots and umbrella-like branches that you can't help but stand beneath and gaze heavenward. What we didn't know is that it is a Liberty Tree, one of the few remaining, planted in 1797 to commemorate the French Revolution.

I heard a lovely story about this tree. Before a fence was erected, I assume to protect the vulnerable roots, whenever the townspeople of Bayeux would walk by it they would pause to kiss their palms and tenderly press them to the trunk of their tree.

Then there is the Cathedral herself. The Bayeux Cathedral is immeasurably grand, ceilings soaring above echoing floors. Entering into such a place gives you a real sense of occupying only a small portion in the procession of time. Like the Bayeux Tapestry, the Cathedral has survived much. Thank heaven, (literally I suppose), it, and Bayeux, were spared the bombings of the WWII.

When we visited the great lady, a pipe organ lesson was taking place, the young man intermittently filling the immense space with sometimes tentative, sometimes majestically thundering hymns and rolling walls of sound.

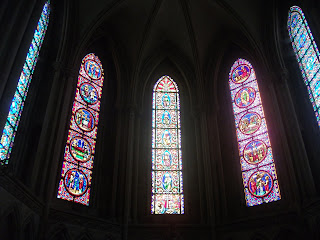

Along the walls were niches, three sided rooms, each dedicated to a saint or soldier, prayer and gratitude, and candles for lighting. Stained glass windows with their rainbow devotions overhead, graves beneath our feet. There was so much to see, so much richness, art, carvings, colors, that it was difficult to know where to look. We circled around, peering into gold lidded boxes beneath glass, containing bits of saints, be they bones or carefully wrapped limbs,

paused to admire and add to a glowing table of candles lit for peace, and lit another candle for Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. I am not Catholic, but there is something deeply spiritual in lighting a candle in such a sacred place, adding a bit of firelight to the world.

Perhaps it's my sad, sad attempt at a French accent. Sigh.

Or the hair.

Either way, I donated another few euros for the pamphlet in the correct language at the self-serve station out of sight from the nice lady with the strong will, and figured it was all going to a good place.

Beneath the floors of the cathedral also resides the crypt, a place of mystery and the oldest part of the cathedral. It was quite dark down there, actually, only muted light from outside from one and though I hate to use the flash, especially with a nod to not causing light damage, there were no signs prohibiting it and I honestly couldn't see. So I took two photos to get an idea of what was down there. Here's one.

There was something that resonated with some ancient part of my psyche, seeing that angel, being underground with that being, prickled the hairs on my neck. There was power in that ancient face, something awesome in the old, biblical sense of the word.

Can you imagine how a villager, illiterate and full of the fear of God, might have felt in the Middle Ages, passing through the glories of the cathedral and then entering the crypt among the dead?

We missed so much in the cathedral, simply not knowing what to look for and being overwhelmed regardless. We did stumble across the tribute to a Yale boy, from Chicago named A. Peter Dewey who parachuted into France with the OSS in 1944 and then became the first American fatality in Vietnam (then French Indochina) in 1945.

but utterly missed the stained glass window of the patches from all the British units that were in the invasion.

that little person there in the blue would be me, to give you some size perspective

Every time we went anywhere near the Bayeux Cathedral Mike and I were astounded anew by the artistry, the glorious transcendent presence of this holy lady.

Isn't it amazing that there are places like this in the world, that have survived so much, and endure?

Bayeux Cathedral, nighttime

Dick Winters, along with many others in the 101st, donated his gear (above) to the Dead Man's Corner Museum, St-Côme-du-Mont.

Dick Winters, along with many others in the 101st, donated his gear (above) to the Dead Man's Corner Museum, St-Côme-du-Mont.

The assault on Brécourt Manor is still taught today at West Point Military Academy as a classic example of tactics and leadership for a small force to overpower a larger one. The Howitzers posed a major threat to the landings at Utah Beach, and had they not been taken out, many more lives would have been lost.

The assault on Brécourt Manor is still taught today at West Point Military Academy as a classic example of tactics and leadership for a small force to overpower a larger one. The Howitzers posed a major threat to the landings at Utah Beach, and had they not been taken out, many more lives would have been lost.

Mike at the site of the one of the Horsa Glider positions,

Mike at the site of the one of the Horsa Glider positions,